By Dr. Brooks Robinson/Black Economics

Photos: YouTube Screenshots

Physical relocations typically come with different state and local government tax structures and provision of public goods and services. Given the advanced state of the US economy, does it not seem logical that experts would identify an ideal level of public sector output that could serve as the gold standard for all state and local governments and sufficient revenue could be generated to finance fulfillment of standard? Yet we know too well that we do not exist in an ideal or perfect world. Therefore, this brief analysis generates interesting insights concerning local and state governments, their economic efficiency, and about differences in outcomes across governments that might inform decisions to relocate—especially quality of life outcomes.[1]

Why do different governments provide varying levels of public sector output?

There are many responses to that question. However, the responses should include the adage: “All politics is local.” Governments operate under the cover of a political system, and the political economy prevailing at local and state levels plays an important role in determining the features and volume of public sector output.

One could then rattle off a list of “sub-determinants” of public sector output: e.g., Hysteresis (tradition’s momentum); location (latitude, topography, and proximity to other governments); area (land and water); existing social/cultural/human capital; ethnic/political/industry concentration (i.e., the extent to which an ethnic group, political party, and/or industry can impose its will on the remaining elements of the population); and etc.

Irrespective of the underlying reasons for a particular public sector output set, residents experience the utility or disutility of that output, which can be characterized or measured by a “quality of life” metric.

Why does any of this rise to a level of importance for Black Americans?

On one hand, it is simply important to be awake to the reality of our socioeconomic and political environment and the underlying factors that cause and sustain them. On the other hand, US media are engaged currently in convincing Black Americans that our best future lies in the US South. Also, rich and famous Black Americans are helping to hammer home this message. When one encounters such circumstances (i.e., government, media, or popularly recognized and “accepted” personalities promoting an identical message) it behooves those who will be affected by the message to do a little digging.

We dug beneath the surface to answer certain questions about a small set of local and state governments to comprehend their fiscal outcomes and their related determinants. An important objective was to determine whether southern governments are associated with public sector output and expenditure outcomes that Black Americans might prefer.

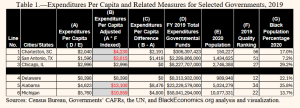

We sought to measure the economic efficiency of three local (populations of 150K, 1.5M, and 3.0M) and state (populations of 1.0M, 5.0M, and 10.0M) governments. The six governments were selected from lists of US cities and states by population such that their populations matched closest to the just identified six populations. The economic efficiency metric of choice was total expenditures (total operational and capital expenditures from governmental funds) per capita. Given economic uncertainty and volatility since the onset of the Covid-19 Pandemic in 2020, we chose 2019 as the period for analysis. Population statistics are from the US Census Bureau, and expenditure statistics are from governments’ Consolidated Annual Financial Reports, which are readily available on the Internet. Table 1 reflects the results of our statistics gathering.

On an unadjusted basis, column A of Table 1 shows San Antonio to be the most cost-efficient government among cities, and Alabama to be the most cost-efficient government among states. Notably, the variation in expenditures per capita motivates the question: Which differences exist between state and local governments that create a $1,400 gap for cities and a $3,775 gap for states bottom to top. Again, many reasons are likely to be relevant, but these differences invite the question: “Is the quality of life in these cities and states significantly different?”

To answer the latter question we identified independent measures of the quality of life for these governments. For cities, we obtained the 2019 US Cities Sustainable Development (SD) Report, which emanated from the United Nations’ (UN) Sustainable Development Goals Program.[2] For states, we obtained Human Development Indexes (HDI), which also represent a UN effort to measure quality of life.[3] We captured the 2019 scores for the three cities and three states from these sources (column E of Table 1). For cities and states separately, we indexed the three scores normalizing on the highest (best) scores government as the numeraire, and then applied each government’s indexed value to its expenditures per capita in column A to produce adjusted expenditures per capita in column B.

Column F shows that Chicago and Delaware reflect the best (highest value) quality score. Accordingly, columns B and C reflect imputations for the additional government expenditures required to, theoretically, lift the quality of life in Charleston and San Antonio to the Chicago level. Similarly, spending increases would be required to lift the quality of life in Alabama and Michigan to the level prevailing in Delaware. While the spending differences required to bring quality to parity across the cities and states on a per capita basis may seem small, the additional spending requirement would be sizeable when applied to the entire population.

An additional and important insight from Table 1 is that three (Charleston, San Antonio, and Alabama) of the four southern governments (Delaware being the fourth) in the table reflect the poorest city and state quality scores. Yet, such scores have not motivated Black Americans to abandon altogether residency with these three governments: i.e., the percentage of Black Americans in Charleston and Alabama exceed the national average of 12.0%, and Black Americans in San Antonio constitute 7.2% of the population.

This brief analysis just scratches the surface in exploring fiscal outcomes for a small group of city and state governments. However, it is at least partially indicative of analyses that should be performed when forming, evaluating, and promoting specific economic behaviors for Black Americans. This is especially true when the socioeconomic condition of Black Americans is in desperate need of improvement. It does not seem proper and right to place the long-term future of Black America at risk by suggesting actions and only alluding to expected political outcomes that, where they already exist, have not produced vigorous and radical change that is predicted and required to hew out and pave a smooth road to Black America’s rightful place among the world community of nations.

Given Table 1 data alone, one could extrapolate that southern US governments may present an economically (cost) efficient fiscal profile on an unadjusted basis; however, the quality of life that they offer may be superseded by governments elsewhere in the country. Consequently, moving south could yield unfavorable quality of life outcomes for Black Americans, which is clearly an economic concern. However, it is just one of the myriad topical areas that should be analyzed before recommending actions that can impact significantly Black America’s future.

References:

[1 ]This analysis brief follows and builds on our analysis of Charles Blow’s, The Devil we Know: A Black Power Manifesto, Harper Collins, New York, in a March 2024 Analysis Brief entitled, “Moving South;” https://www.blackeconomics.org/BELit/ms032924.pdf (Ret. 070524). The brief calls into question Blow’s insistence on accelerated Black American migration to the US South.

[2] A. Lynch, A. LoPresti, and C. Fox, (2019), The 2019 US Cities Sustainable Development Report. Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN), New York; https: www.sustainabledevelopment.report/reports/2019-us-cities-sustainable-development-report/ (Ret. 070424).

[3] United Nations (2024), “United States Subnational HDI (Human Development Index, v7.0),” Global Data Lab; https://globaldatalab.org/shdi/table/shdi/USA/ (Ret. 070524).