Photos: YouTube Screenshots

How do you dramatize an intolerable living situation facing thousands of low-wage hospitality workers? You take it to the streets – nonviolently.

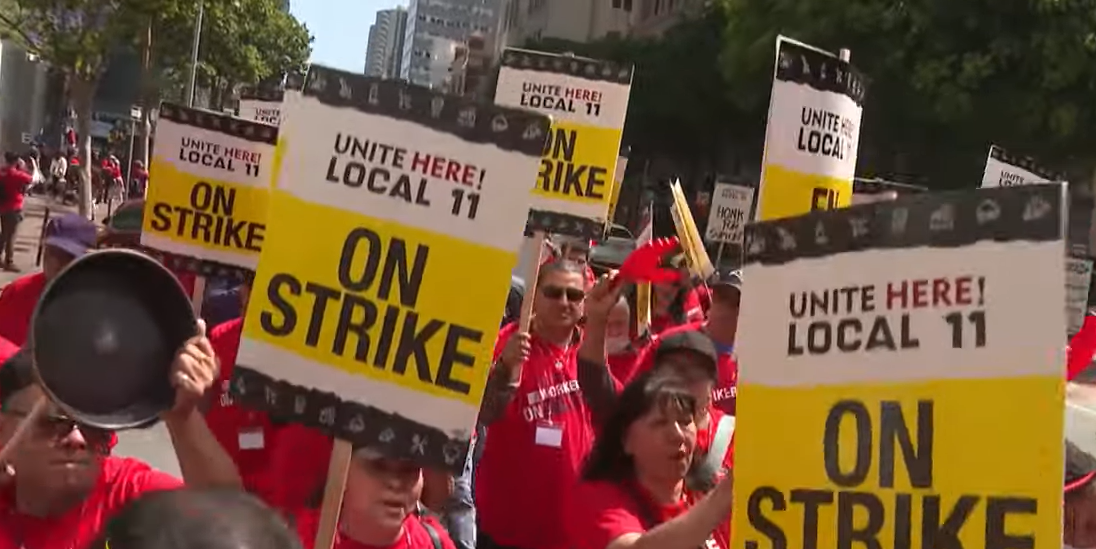

That’s what the workers of UNITE HERE Local 11 did on Thursday, June 22, shutting down a major artery leading in and out of Los Angeles International Airport (LAX), the sixth busiest in the world, and using that boulevard to rally and to launch a sit-down protest that led to the arrest of almost 200.

Hundreds of LA workers showed up to draw public attention to the combined burden of high housing costs and low wages in the city (A two-bedroom apartment in LA costs around $2183 per month, while hourly wages for housekeepers run from $20-$25 hourly). To make ends meet, many workers labor at second and third jobs, while others have moved north and east of the city to find affordable rents, commuting up to two or three hours each way. Personal time, family life, sleep: all are squeezed into ever diminishing segments of time. Hardships like these were voiced powerfully by one speaker after another at the June 22 action.

But there’s a larger story behind this action, a 30-year story that gives context and meaning to the events of June 22. It’s a story involving the union’s close identification with nonviolence, an identification that has made UNITE HERE Local 11 a powerful change agent within the city. In the late 1980’s, under the leadership of a new president, Maria Elena Durazo, the union began drawing on the strategies and teachings of nonviolent activists and teachers like Cesar Chavez and the Reverend James M. Lawson, Jr., the latter having moved to Los Angeles from Memphis in the early 1970’s.

Under Durazo’s leadership, and the leadership of those who followed her, the union started using creative modes of street theater and other forms of protest to engage workers and to build strong coalitions with community organizations. As it did so, Local 11 began incorporating an ethos of nonviolence and movement justice that recognized the worth and dignity of every worker, no matter what their immigration or citizenship status.

The change catalyzed a transformation in attitudes toward the city’s immigrant workers who, then and now, constituted a substantial proportion of LA’s low-wage workforce. The transformation has been embodied in such union practices as transparent bargaining, in which workers have been welcomed into contract negotiations, describing their experiences and presenting their demands directly to management. One observer has described such negotiating as a form of “democracy in action.”

Seventeen years ago, on September 28, 2006, almost 3000 workers and community allies blocked off Century Boulevard (the same LAX artery blocked this past June 22), demanding passage of three ordinances (including a living wage ordinance) protecting workers’ rights as well as union recognition by LAX-area hotels. The action, which led to the arrest of elected officials and numerous civic and religious leaders, helped bring about the passage of the three ordinances as well as union recognition by four LAX-area hotels.

Now, 17 years later, Local 11 members have voted to authorize a strike should current negotiations fail in the face of contract expiration on June 30. But this time, 62 hotels are involved, not four, as the union has steadily grown over time. A strike this year would mean 15,000 workers walking off the job, demanding an immediate wage hike of $5 per hour, followed by $3 per hour for each of the remaining two years of the three-year contract. Other bargaining demands include provisions for health care, pensions, workload, and a hotel surcharge dedicated to a fund for affordable housing for workers.

By most recent reports, the hotels have proven intransigent in response to these demands, and the fight may prove to be a long and difficult one. But the workers understand the power of a strike that could cripple a tourist industry that brought 46.2 million people to Los Angeles last year and $21.9 billion in revenues to Southern California. And the workers well know that the World Cup is coming to LA in 2026, followed by the Olympics in 2028.

It is difficult to express adequately the tangible spirit of solidarity at a protest like that of June 22: the drumming and the chanting (“Si se puede!” “Huelga!”); the presence of hundreds of workers and family members in the red T-shirts of UNITE HERE Local 11; the presence of clergy of all denominations in their collars and robes; and the joining of elected officials with workers and other community members in the sit-down protest on Century Boulevard. The mood was both celebratory and defiant. As one union leader told me, “Welcome to our first summer block party!”

As the afternoon faded into early evening, and as the cadre of more than 50 police took up positions to begin arresting the protesters, a truck passed by on the narrow peripheral road adjacent to Century Boulevard. Emblazoned on its sides were the words, “LA IS A UNION TOWN.”

It’s inconceivable that a message like that would have borne any resemblance to the truth just a few decades ago.

But times have changed – and they continue to change. It is unions like Local 11, grounded in the ethos and strategic vision of nonviolence, that are moving the clock of justice forward.

Andrew Moss, syndicated by PeaceVoice, writes on labor and immigration from Los Angeles. He is an emeritus professor (Nonviolence Studies, English) from the California State University.