Photos: YouTube

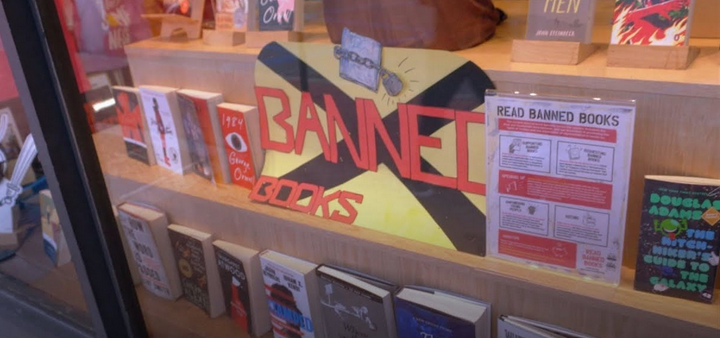

(ST. LOUIS)— Missouri has banned nearly 300 books in at least 11 school districts since August, PEN America said today and— joined by over 20 authors and illustrators, including prize winners and best-sellers like Margaret Atwood, Art Spiegelman, Lois Lowry and others— called on school districts to immediately reverse the bans and return all books to library shelves.

School districts have banned works on Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, graphic novel adaptations of classics by Shakespeare and Mark Twain as well as The Gerrysburg Address, the Pulitzer-prize winning Maus, and educational books about the Holocaust. Also banned have been comics about Batman, X-Men, and Watchmen; The Complete Guide to Drawing & Painting by Reader’s Digest; Women (a book of photographs by Annie Leibovitz); and The Children’s Bible. The complete list of books banned in Missouri records 297 books across the state.

In an open letter, the authors and illustrators joined PEN America in protesting the sweeping book bans, saying the removal deprived students across Missouri of the freedom to read. The books were banned in response to a new law, SB 775, that makes providing “explicit sexual material” to students a class A misdemeanor, punishable by a penalty of up to one year in jail and a $2000 fine for those convicted. The law went into effect in August.

Although the law makes pedagogical exceptions for materials that have artistic or anthropological significance or are used in science and sexual education classes, at least 11 school districts have banned nearly 300 books since August. In one district, over 220 books came off library shelves for an indeterminate period of “review.”

“Even amid an avalanche of book bans this fall, the removals in Missouri stand out,” said Jonathan Friedman, director of free expression and education programs. “These districts–and likely others–have deputized themselves censors, sweeping up in a dragnet all manner of educational materials often with little documented justification. These districts seemingly sought to purge any potentially offending visual material to avoid running afoul of the new law. In so doing, they have cast aside the rights of students to read and learn, as well as the fundamental mission of public education and school libraries.”

Authors and illustrators who signed the letter also include: Neil Gaiman, Roxane Gay, Alison Bechdel, Carmen Maria Machado, Laurie Halse Anderson, M.T. Anderson, Derf Backderf, Khalil Bendib, Matt Bors, Ellen Crenshaw, Mike Curato, Juno Dawson, Evan Dorkin, Deborah Hopkinson, Miles Hyman, Kelly Jensen, Lita Judge, Rupi Kaur, Maia Kobabe, Dylan Meconis, Ryan North, David Small, Amir Soltani, and Colleen AF Venable.

In urging school districts to reverse the bans, the letter states: “Such overzealous book banning is going to do more harm than good. Book bans limit opportunities for students to see themselves in literature and to build empathy for experiences different from their own. They deprive students of the freedom to read–to think, to imagine, to grow. And photographs and illustrations can be vital to storytelling: a window into the past, a means of reflecting the human condition, a tool for helping reluctant readers engage with literature.”

PEN America has created an explainer about the new law and the sweeping bans.

The full letter is below:

To Missouri School Boards and Districts,

We, the undersigned, join authors, illustrators, and the literary and free expression organization PEN America, to protest the alarming book bans that have been enacted in Missouri schools this fall. These bans represent a grave threat to the freedom to read, much to the detriment of students across the state.

These bans have been enacted largely in reaction to a provision in Senate Bill 775, which makes the distribution of material deemed “harmful to minors” to students in Missouri by any school official (educators, librarians, student teachers, coaches) or by any visitor to a school, a misdemeanor punishable by fines or jail time.

What is the definition of “harmful”? Who decides? The new law focuses on “visual depictions” and “sexual material,” and some school boards and officials have interpreted it broadly, removing an astonishing range of material: dozens of graphic novels and comics, books with photography, memoirs, and books about art history. In the ten weeks since the provision went into effect, at least 11 school districts have banned over 300 books. Several districts banned books from their libraries permanently. In one district, over 200 books came off library shelves for an indeterminate period of “review.”

Provisions in the law that exempt materials of artistic or anthropological significance are clearly being ignored. Students have been barred from checking out works on Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, graphic novel adaptations of classics by Shakespeare and Mark Twain as well as The Gettysburg Address, the Pulitzer-prize winning Maus, and other books about the Holocaust. Districts have banned comics about Batman, X-Men, and Watchmen; The Complete Guide to Drawing & Painting by Reader’s Digest; Women (a book of photographs by Annie Leibovitz); and The Children’s Bible.

Such overzealous book banning is going to do more harm than good. Book bans limit opportunities for students to see themselves in literature and to build empathy for experiences different from their own. They deprive students of the freedom to read–to think, to imagine, to grow. And photographs and illustrations can be vital to storytelling: a window into the past, a means of reflecting the human condition, a tool for helping reluctant readers engage with literature.

Students in Missouri are having these educational opportunities denied. They are bearing the brunt of a hasty and poorly considered reaction to a broadly worded provision that has spurred censorious acts across the state. They are having their right to access a diversity of ideas, information, art, and literature in school libraries diminished.

We urge school district officials in these 11 districts to reverse these dangerous bans, and to put materials back on shelves where students can regain access to them.