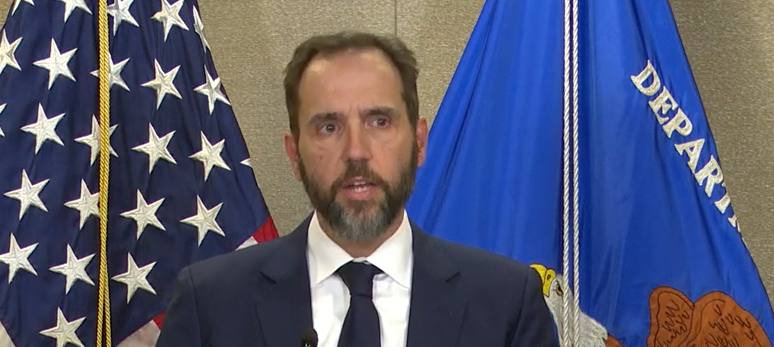

Photo: YouTube

Dwight Eisenhower appointed Bill Brennan to the Supreme Court, sight unseen, because he was a young Catholic Democrat from a swing state, the “Catholic seat” was vacant, and it was an election year. Thank goodness. Brennan went on to become one of history’s greatest jurists.

My employer, the Brennan Center, was created in his honor.

On the wall in my Brennan Center office is a portrait of another personal hero: Louis Brandeis. He was well known at the time of his appointment — dubbed “The People’s Lawyer” before the advent of modern public interest law — but Woodrow Wilson chose him largely to appeal to Jewish swing voters.

Brandeis faced fierce anti-Semitic opposition. Sen. Henry Cabot Lodge privately complained, “If it were not that Brandeis is a Jew, and a German Jew, he would never have been appointed.” (Lodge, of course, also authored the important voting rights bill to protect the rights of Black Americans, which was defeated by a filibuster in 1890. History is complicated.)

Representation is part of the Supreme Court nomination process. As has been noted, Ronald Reagan promised to appoint a woman, and he did. Not all representation is good, of course. Asked about Nixon nominee G. Harrold Carswell, Sen. Roman Hruska memorably replied, “Even if he were mediocre, there are a lot of mediocre judges and people and lawyers. They are entitled to a little representation, aren’t they, and a little chance?” That “praise” more or less doomed the nomination.

Supreme Court nominations intended to make the Court look a bit more like the country it serves have a long provenance. And they are often accompanied by a dollop of overblown indignation.

So let’s not be surprised when some people huff and puff about President Biden’s commitment to nominate a Black woman to the court.

The value of diversity in the judiciary is unarguable. Studies have shown that greater representation of Black judges on the bench heightens the perceived legitimacy of the court among Black Americans, and that judges with different life backgrounds often issue different rulings. As my colleague Alicia Bannon and Douglas Keith write, “[T]he answers to difficult legal questions, especially those that reach the Supreme Court, demand good judgment — and that is necessarily informed by life experience.”

Soon we will know who the nominee is. Any of the names most prominently floated — Kentaji Brown Jackson, Leondra Kruger, or J. Michelle Childs — are superbly qualified. I may be wrong, but I have a sneaking suspicion that the nominee will have a relatively easy time of it.

In part that is because, as admirable and history-making as such a choice would be, it will not change the fundamental fact about the Court. It is now dominated by a hyper-conservative supermajority, the first time in decades that an ideological faction has the Court so firmly in its grip.

Already last July the justices gravely undermined what was left of the Voting Rights Act. By inaction they have allowed Texas, the second-biggest state, to effectively outlaw abortion.

They appear poised to greatly expand gun rights and overturn Roe v. Wade — all by the time the next justice takes her seat.