Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The predominant direction of a progressive US president should be toward “Making America Safe for the World.”

That means focusing on domestic problems rather than on foreign policy crusading, relying on diplomacy before making threats and imposing sanctions, redefining the national interest with an eye toward real friends and urgent issues, and finding common ground with adversaries, starting with China, while remaining faithful to our ideals.

These priorities offer a window on specific issues that confront the Biden administration’s foreign policy team.

The “Power of Example”

Joe Biden has proposed, rightly I think, that the “power of example” offers the best way to promote democracy and human rights abroad. It’s an idea that actually goes back to the founding of the republic.

But America’s post-World War II predominance has led one administration after another to espouse opposing ideas: “American exceptionalism,” “the city on the hill,” and presumed “universal values.” These have promoted a global military presence, disastrous interventions abroad, and bloated military budgets and arsenals.

The US needs to return to the founders’ notion of America as “a shining example”—a country that wins friends and influences people by demonstrating that liberal democracy works at home.

Let others see that the Trump years were an anomaly and the January 6 mob attack an outrageous assault on the popular will. Let them be emboldened to contrast constitutional governance, respect for human rights, and lawfulness with authoritarian and popular nationalist models—models that, as we see in China, Russia, and Europe today, cannot accommodate the rule of law, ethnic and cultural diversity, and open dissent.

Biden’s democracy restoration project already faces a contradiction, however. He seems bent on calling for a Summit for Democracy which, according to one observer, is intended “as a way to restore America’s historic, if selective, role as the world’s premier beacon and champion of liberty.”

Biden says the summit would “bring together the world’s democracies to strengthen our democratic institutions, honestly confront the challenge of nations that are backsliding, and forge a common agenda to address threats to our common values.”

This is a bad idea. Leaving aside the question of which countries would qualify as democratic and share “common values”—Philippines? Turkey? Egypt? Brazil? Hungary?—the key problem is America’s credibility. At the moment the US is anything but a beacon of democracy to the world.

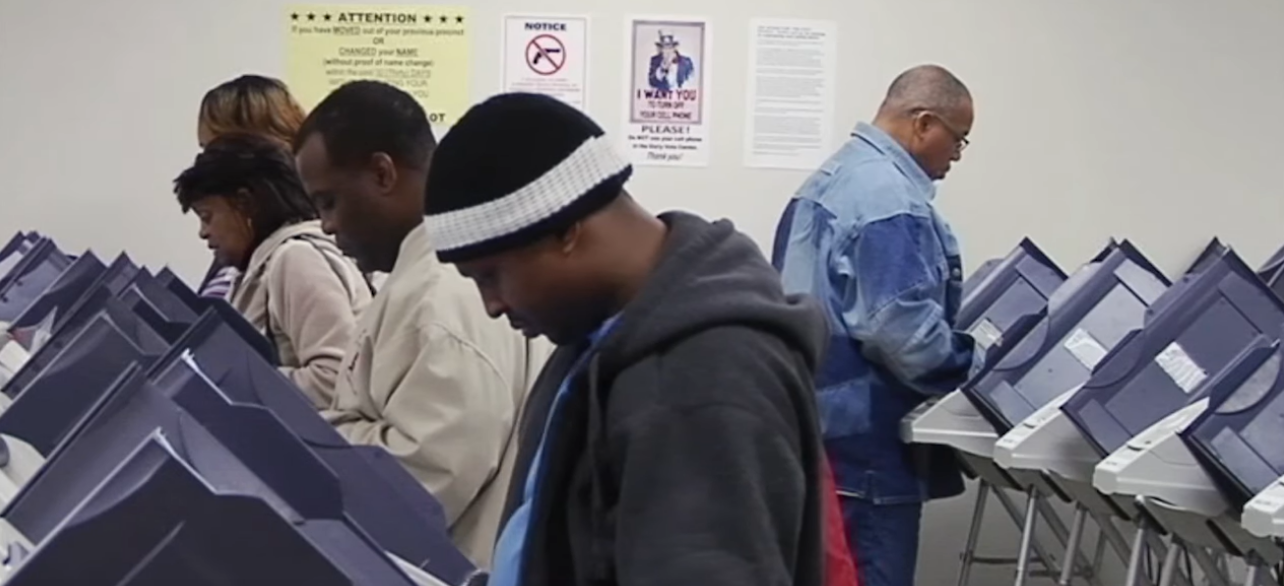

We have to prove our worth as never before, and that requires giving priority to a domestic agenda that includes restoring the balance of power between the three branches of government, practicing adherence to the Constitution, promoting racial justice, and dealing forcefully with violent extremist groups and their enablers in Congress. Summit speeches are no substitute for demonstrated faithfulness to the American democratic ideal.

A summit on rebuilding democracy in America might be more meaningful—a convocation of civil society groups as well as government agencies at all levels.

One focal point would be how best to combat domestic terrorism and other forms of political violence. Systemic racism, voting rights, immigration reform, and Congressional dysfunction would be other topics. Democracy American style is failing under the weight of self-interested politics, social division, and economic inequities. We may have admirable ideals, but nothing to export at the moment.

Engaging Adversaries

The rebuilding of America thus comes first, but foreign affairs cannot be put on the back burner. Biden has already restored US involvement in the Paris climate accords and the World Health Organization.

In time he will attend to repairing relations with allies and building coalitions in response to global problems such as the pandemic. Fine; but Biden needs to deal quickly with the tense state of relations with Russia and China.

With Russia, calling out Moscow’s election interference and cyberwarfare should not keep Biden from getting the US back into nuclear arms control.

Biden should agree to a five-year extension of the New START and to renewing the Open Skies treaty. Likewise with China, it is all well and good that he sharply criticizes the Xinjiang “genocide” (as he rightly calls it), repression in Hong Kong (“Beijing’s crackdown on democracy,” Antony Blinken, the nominee for secretary of state, says), and pressure on Taiwan. But those positions should not stand in the way of seeking (actually, rediscovering) common ground with Beijing on pandemics, global warming, trade, and maritime security.

President leadership will be central to relations with these adversaries, and Biden will have to resist political pressures, including from his own bureaucracy and party, to combat reemerging Cold War thinking.

On Russia, one seasoned former US intelligence official, Angela Stent, who served under George W. Bush, has pointed out: “This will be the first post-Soviet U.S. administration that has not come into office vowing to forge a warmer relationship with Russia.”

The same might be said of China policy: Starting out with strong rhetoric and nothing else only invites angry retorts from the Chinese side, further envenoming a relationship already badly damaged under Trump.

Blinken has vowed to follow the basic lines of Trump’s China policy. If that means decoupling trade and continuing Mike Pompeo’s ideological war on the Chinese Communist Party, we’re in for an intensified strategic competition that will not benefit US allies in East Asia or Europe, and may well increase the possibility of war.

Breaking with the Past

A progressive foreign policy often requires breaking with past policies and practices that do not serve either the human interest or the country’s real security needs.

Under Biden, the US needs to return to the Iran nuclear deal, as he has promised though with conditions. He also needs to reverse the policy of “maximum pressure” on both Iran and North Korea—a policy that really amounts to regime change.

With Iran, Biden should resist Israeli and Saudi pressure and explore opportunities with Tehran beyond the nuclear issue, such as resumption of trade and investment, a political settlement in Yemen, and Iran’s involvement in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria. Biden should further demonstrate the new look in US Middle East policy by distancing the US from authoritarian governments in Turkey and Saudi Arabia (including ending the Saudi role in Yemen), no longer catering to the Israeli right wing’s apartheid and territorial ambitions, and explicitly rejecting drone warfare.

As for North Korea, which is continuing to work on its strategic weapons capabilities despite admitted economic failures, the Biden team should not neglect engagement possibilities. In the last year of the Trump administration, Kim Jong-un’s warnings went unheeded, and as a result the regime’s long-range weapons now include a submarine-launched missile.

Biden needs to come up with incentives, such as gradual removal of sanctions timed to nuclear threat reduction. Failure to pay attention to Kim’s moves will surely create another—avoidable—nuclear crisis.

Global warming is in the care of John Kerry, a very good thing indeed, as is returning to the Paris accords and making plain that climate change is a national security priority.

But questions remain. What can and will Biden do to bring about a rapid reduction in carbon dioxide emissions? What specific commitments will Kerry make at the next international meetings on climate change? China has shown leadership on global warming with ambitious plans for alternative energy and carbon dioxide reductions.

Will Biden come through on a Green Economy plan that captures worldwide attention? The ball is in Washington’s court.

Then there’s the matter of America’s nuclear arsenal, still measured in an overabundance of long-range warheads and delivery vehicles.

If Biden wants to get serious about this issue, he should listen to the advice of William J. Perry, the former defense secretary. Perry is among those former officials, such as Henry Kissinger and the late Robert McNamara, who have long argued for dramatic reductions in the US nuclear arsenal, down to a minimal deterrent force.

Perry now supports a further step: that the US sign and ratify the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, which just became international law when the fiftieth state ratified it. Neither the US nor any other nuclear-weapon state has signed the treaty, but as Perry explains, it is

“a new instrument of non-proliferation, augmenting the existing Non-Proliferation Treaty. It offers powerful support to those arguing against modernizing and expanding nuclear arsenals, actions that will now fail to follow the international law that most countries have agreed to live by. The treaty won’t end nuclear weapons any time soon, but it represents an important step in that direction.”

Biden’s signature, and Senate ratification, would be a major boost to a world without nuclear weapons.

Last Thoughts

“Making America Safe for the World” turns traditional US foreign policy on its head. Where economic, political, and military globalism has long driven national security planning, we now have a president who seems to believe that domestic security, starting with ending the pandemic and reviving the economy, is central to national security.

The chief danger for Biden lies at home: He must not succumb to the bipartisan trap—political pressures that would have him adopt hard-line positions on Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea, maintain failing policies in the Middle East, and make only modest changes on energy, environmental policies, and the military’s budget and capabilities.

This is the time to strike out in new directions. The long period of American predominance is over, and US leadership on accountable government and human rights is in doubt. It is all to the good that we have a return to “normalcy,” but normalcy should not mean staying the course.

Andrew Bacevich, a leading foreign-policy critic, writes that Biden’s team is unlikely to go beyond restoring the guidelines of liberal internationalism. He offers some policy specifics that he doesn’t expect to see implemented under Biden:

“persuading Congress to repeal the 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF); definitively ending the endless Middle East wars; reducing the US military footprint overseas; scrapping the trillion-dollar-plus modernization of the US nuclear strike force; converting the armed forces into an instrument of national defense rather than of global power projection; cutting the Pentagon budget to free up resources needed to fulfill Biden’s ‘build back better’ vision of domestic renewal.”

Bacevich’s message is worth underscoring: Unless Biden is prepared to redefine national security, it will not have the resources or the public support to put real security first.

Mel Gurtov, syndicated by PeaceVoice, is Professor Emeritus of Political Science at Portland State University and blogs at In the Human Interest.