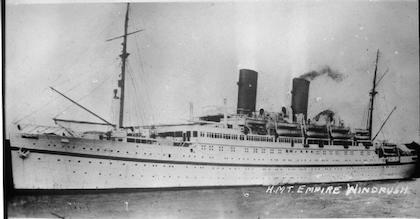

Windrush. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

Imagine living in a country for over half a century only to suddenly be told: pack your bags and prepare to leave immediately, and if you can’t leave in a timely manner you’ll be put in a detention center to await deportation. Due to an oversight made decades ago, you do not have documentation proving legal right to remain in the country. This predicament befell many residence in the U.K. of Caribbean decent just a few years ago. Families who knew no other life apart from the ones they had built for themselves in the U.K. swiftly found that they had become the bane of a very unfriendly British government determined to send them back to the Caribbean, with a very hostile policy designed to ensure a difficult path for any challenges that might be launched by lawyers on behalf of the affected groups and individuals.

Most of the people caught up in this debacle were the Windrush generation; but a few from other countries other than the Caribbean were also ensnared in this scandal. The Windrush scandal is a 2018 British political scandal concerning people who were wrongly detained, denied legal rights, threatened with deportation, and, in at least 83 cases, wrongly deported from the U.K. by the Home Office. Many of the affected had been born British subjects and had arrived in the U.K. before 1973, particularly from Caribbean countries as members of the “Windrush Generation”—so named after the Empire Windrush, the ship that brought one of the first groups of West Indian migrants to the U.K. in 1948.

The British nationality Act 1948 gave citizen of the United Kingdom and colonies status and the right of settlement in the U.K. to everyone who was at that time a British subject by virtue of having been born in a British colony. The Act and encouragement from British government campaigns in Caribbean countries led to a wave of immigration between 1948 and 1970. Nearly half a million people moved from the Caribbean to Britain, which in 1948 faced severe labor shortages in the wake of the Second World War. The immigrants were later referred to as “The Windrush Generation.” Working age adults and many children travelled from the Caribbean to join parents or grandparents in the U.K. or travelled with their parents without their own passports.

Since these people had a legal right to come to the U.K., they neither needed nor were given any documents upon entry to the U.K., nor following changes in legislation laws in the early 1970s. Many worked or attended schools in the U.K. without any official documentation record of their having done so, other than the same records as any UK-born citizen.

Many of the countries from which the immigrants had come became independent of the U.K. after 1948, and people living there became citizens of those new nations. Legislative measures in the 1960s and early 1970s limited the rights of citizens of these former colonies, now members of the Commonwealth, to come to or work in the U.K. Anyone who had arrived in the U.K. from a Commonwealth country before 1973 was granted an automatic right permanently to remain, unless they left the U.K for more than two years. Since the right was automatic, many people in this category were never given or asked to provide, documentary evidence of their right to remain at the time or over the next 40 years, during which, many continued to live and work in the U.K., believing themselves to be British.

Many of them subsequently lost their jobs; others were denied medical treatment, and the banks were instructed not to provide financial services to people who could not prove legal residency. Some who had travelled to see relatives in the Caribbean were barred from re-entering the U.K and many were unlawfully held in detention centers and eventually a few were deported from the U.K.

From November 2017, newspapers reported that the British government had threatened to deport people from Commonwealth territories who had arrived in the U.K. before 1973 if they could not prove their right to remain in the U.K. Although primarily identified as the Windrush generation and mainly from the Caribbean, it was estimated in April 2018 on figures provided by the Migration observatory at the University of Oxford that up to 57,000 Commonwealth migrants could be affected, of whom 15,000 were from Jamaica. In addition to those from the Caribbean, cases of people affected who had been born in Kenya, Cyprus, Canada and Sierra Leone were identified in the press.

The calamity saw some British citizens with Caribbean background deported or threatened with deportation, despite having the right to live in the U.K. An inquiry is being launched into the compensation scheme set up for victims of the Windrush scandal. Several victims had died before receiving any payout. Yvette Cooper, Chair of the Home Affairs Committee, has said Members of Parliament were “deeply concerned” about problems with the scheme. She added: “It is immensely important that the huge injustices experienced by the Windrush generation at the hands of the U.K. Home Office are not compounded by problems in the compensation scheme that was supposed to right these wrongs.”

Official figures published in October show that around 12% of Windrush victims claiming compensation have received payouts. At least nine people have died before receiving compensation. Home Office data shows 71 claims have been made for people who have already died, but so far only three have resulted in payments. Last year, the most senior Black member of Home Office staff working on the Compensation Scheme resigned. She told the Guardian the scheme was systematically racist and unfit for purpose. “The results speak for themselves: the sluggishness of getting money to people, the unwillingness to provide information and guidance that ordinary people can understand,” Alexandra Ankrah, a former barrister who was the scheme’s head of policy told the BBC.

Alexandria Ankrah said she resigned because she lost confidence in a program that she alleged was “not supportive of people who have been victims” and which “doesn’t acknowledge their trauma”. Several proposals she made to improve the scheme were rejected, she said. She was troubled by the fact that several Home Office staff responsible for the compensation scheme had previously helped implement the hostile environment policies that had originally caused claimants so many problems.

By the end of October, the compensation scheme had been running for 18 months and only $2.1 million (£1.6 million pounds) had been paid out to 196 people. Officials had originally expected thousands to apply and estimated that the government might eventually have to pay out between $267 million and $668 million the Guardian reports.