[Future Hope Column]

Glick: “It is critical that more and more people of European ancestry in the U.S. appreciate that a hopeful future for them and their families lies in joining together with, not being hostile to, Blacks, Latinos, Indigenous people, and Asian/Pacific Island people.”

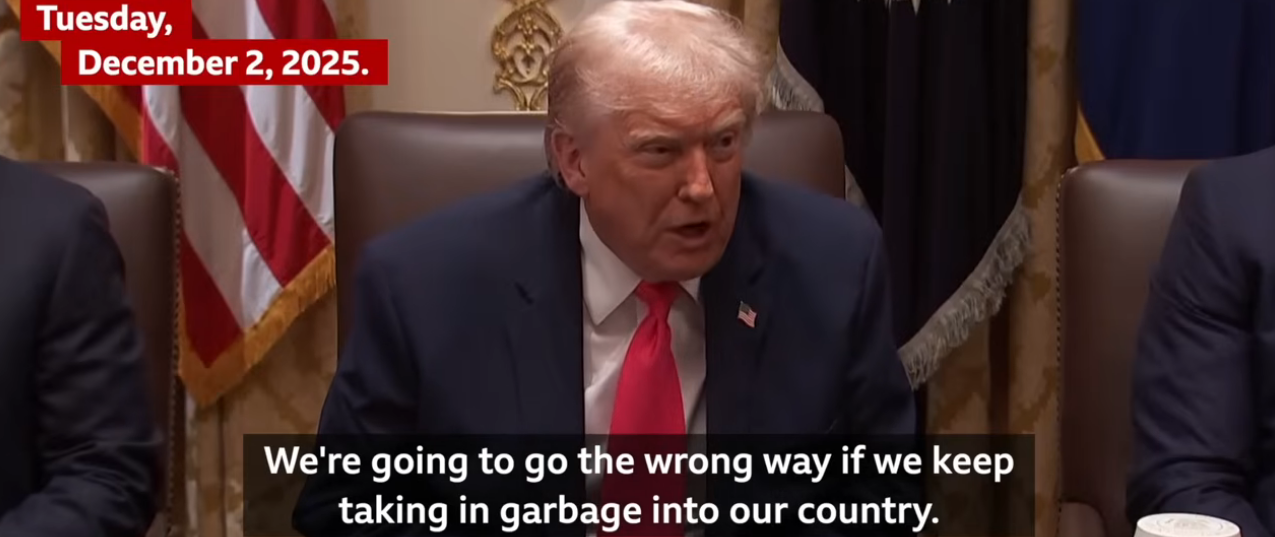

Photo: YouTube

The multi-racial global nature of the George Floyd protests is a hopeful sign that many want a more just America and world.

(This is an excerpt from the “Lessons Learned” chapter of my just-published book, “Burglar for Peace: Lessons Learned in the Catholic Left’s Resistance to the Vietnam War,” available at PM Press. It feels very appropriate to circulate this right now.)

Without any doubt, it was my eleven months in prison [for destroying draft files and other resistance during the Vietnam war] that got me firmly onto the road to consciously attempting on a daily basis to be anti-racist and a strong ally of people of color, because of the many Black and Brown people I met, befriended, and interacted with every day. I already believed intellectually that all people should be treated equally and fairly. In prison, I came to see that all people are, in essence, the same, with similar feelings, ideas, hopes, and dreams.

Prison was also where I very clearly saw the way in which class and race are interconnected. I saw the class system of the prison: at the top, the warden, then the other administrators, followed by the prison guards (with their own hierarchy), the prisoner “trusties,” and the white-collar prisoners, all of whom are very predominantly white. Trusties and white-collar prisoners tend to be the ones who get extra privileges, including work release and single-cell dorms. Finally, there’s the general prison population, a majority of which are Black and Brown. Seeing this in prison left me much better equipped to understand the class/race structure in society at large. It’s not as stark and clear-cut, but it’s definitely there.

Ever since, I’ve tried to put these understandings into practice, taking action and speaking out in support of genuine equality, true justice, and human rights for all people. This has meant participation in more demonstrations than I can remember against police killings or beatings of people of color. In 1999, after Amadou Diallo was shot forty-one times, I was arrested in front of the New York City police headquarters, joining with others to call for a swift indictment of the police officers responsible. From 1993 to 2001, it meant fasting for the first twelve days of every October for freedom for Leonard Peltier and for Columbus Day to be renamed Indigenous Peoples Day. It has meant speaking up at meetings when something has been said that is overtly or subtly racist. Sometimes I don’t do so, truth be told. It’s not always easy, and my fear sometimes wins out over my best intentions.

It has meant joining organizations that are predominantly African-American and following, and sometimes taking part in, those groups’ leadership. And it has meant continuing to wrestle with whether I am doing enough, whether I should be doing something more or something else, whether I really am being a good anti-racist ally.

There’s a particular responsibility that those of us who are white have in this work—the responsibility to interact with and organize among white people, particularly low-income and working-class white people, those who should be more open than they sometimes are to the message that to improve their living conditions, they need to join with working people of all races and cultures. We need to help them realize that white supremacist ideology in particular, as well as other divisive and oppressive ideologies and practices, are not in their best interest.

To sharpen the point: white progressives need to be willing to intelligently risk being uncomfortable, unpopular, or even victims of psychological or physical abuse for speaking up among a predominantly white group of regular folks. I don’t mean so much a predominantly white group of progressives, though there are often subtler, less overt issues there too. I am talking about average working-class or middle-class white people.

Usually, in that kind of setting, sooner or later, there’s going to be white supremacist ideas expressed. That’s not necessarily because the group as a whole or the person(s) expressing them are hard-core KKK members. It’s because, as the mass response to the racist (and everything else) Trump campaign and presidency has shown us, white supremacy is very much alive and well among a huge portion of the U.S. white population.

It is critical that more and more people of European ancestry in the U.S. appreciate that a hopeful future for them and their families lies in joining together with, not being hostile to, Blacks, Latinos, Indigenous people, and Asian/Pacific Island people. It was put this way in a 2016 statement by the group Showing Up for Racial Justice:

“While people of color bear the brunt of racism, large numbers of white people have also been failed by the system—facing job loss, inadequate housing and cutbacks in core services. Instead of addressing real fears and insecurity, racist elites actively target white working class white people into blaming people of color for the problems their families and vulnerable communities face.”

How Whites Organize Whites

This is also critical.

Guilt-tripping isn’t the way to do it. People who act primarily because they are feeling or have been made to feel guilty about their whiteness are people who are going to have a hard time interacting with whites who are suffering economic hardship or the white masses in general. Instead, while acknowledging the legitimacy of guilt felt over the historically brutal violence, oppression, and discrimination by huge numbers of white people, generally, against Indigenous, African, Mexican, and Asian peoples, we, as whites, must move past guilt. We need to be clear that white supremacy also hurts white people, engenders guilt and fear, for example, and makes united action on common issues like housing, healthcare, or the right to organize more difficult.

It’s also critical that whites organizing whites take up the economic, health care, education, or other issues impacting predominantly white communities, to show that they are concerned about all forms of inequality and want a just society for everyone. This is key. A good organizer knows that you need to start with people where they are, make connections on the basis of issues, experiences, or other things held in common. As those connections are made, as people get to know and respect the organizer, they are more willing to listen and think about constructive criticism from her/him/them or ideas other than those they are ordinarily exposed to.

Finally, white organizers who are serious about anti-racism need to have ongoing connections to people of color, by participating in a multicultural organization of some kind, at a minimum. It is better if that happens at the same time that healthy friendships are developed with individual people of color. We, as whites, need ways to be continually reminded about how white supremacy works. We need friends of color whom we support and who will support us, who criticize us for things we say or do that reflect our upbringing in a white supremacist culture and help us to develop into better and more conscious people, better organizers, better and stronger human beings.

Ted Glick is the author of the just published Burglar for Peace: Lessons Learned in the Catholic Left’s Resistance to the Vietnam War. Past writings and other information can be found at https://tedglick.com, and he can be followed on Twitter at https://twitter.com/jtglick.