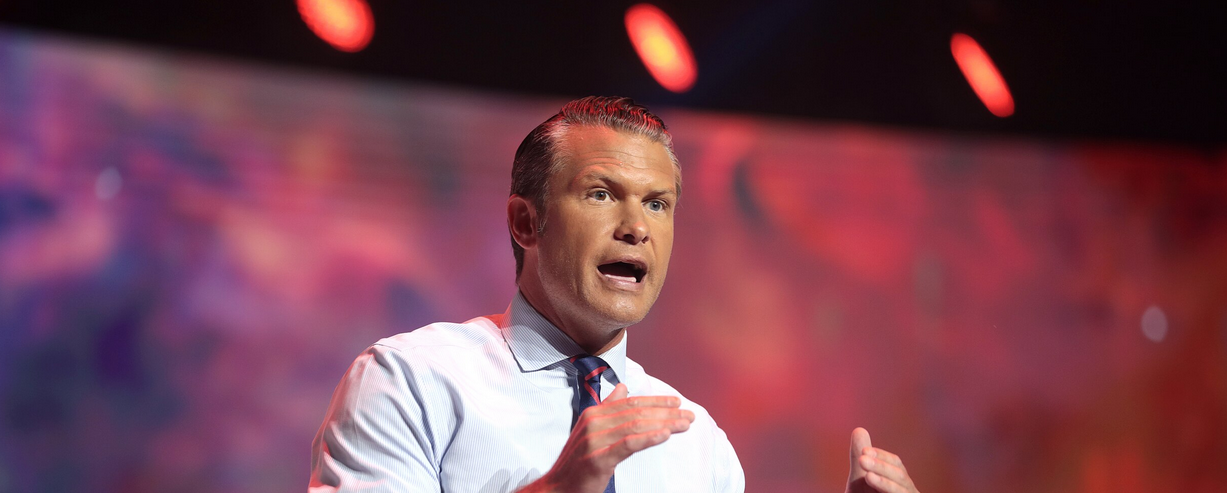

Former Rep. Lee Hamilton

With the 114th Congress just underway, the political world is focused intently on the road ahead. Taxes, trade, immigration, climate change, job creation, the Affordable Care Act there’s a long list of issues and one burning question: whether a Republican Congress and a Democratic President can find common ground.

Yet before we get worked up about what’s to come, we need to take a hard look at the Congress that just ended and ask a different question: Why was it such an abject failure?

Let’s start with a basic number. According to the Library of Congress, 296 bills were passed by the 113th Congress and signed by the President. Just for comparison’s sake, the “do-nothing Congress” of 1947-48 got 906 bills through. The Financial Times called this most recent version “the least productive Congress in modern U.S. history.” The only silver lining was that the cost of running Congress was down 11 percent.

Congress failed most spectacularly on the basics. Not one of the dozen annual appropriations bills passed, while the budget resolution, which is supposed to set overall fiscal policy, never even got to a vote. In both houses, the leaders did what they could to make the legislative body of the world’s greatest democracy as undemocratic as possible. Senate Democratic Majority Leader Harry Reid used legislative maneuvers to block amendments more often during his time as majority leader than any of his five predecessors. In the House, Republican leaders used so-called “closed rules,” which prohibit amendments, a record number of times. Both approaches denied by legislative device the opportunity for Congress to work its will.

When Congress did legislate, it did so in the worst possible way — by using an “omnibus” spending bill into which it crammed everything it could manage. The bill was put together in a single week, guaranteeing minimal study by the members of Congress who voted on it. Ostensibly meant to fund the government through September, it contained a host of provisions that deserved a full airing.

Instead, with virtually no public debate, Congress multiplied the amount of money that wealthy donors can give to the political parties; loosened regulations on Wall Street; cut funding for the Environmental Protection Agency, forcing it to its lowest staffing level in over two decades; and hacked funding for the IRS. This last measure, a gift to tax cheats, was an especially egregious assault on ordinary taxpayers, who will now be asked to foot a bill that robust enforcement of the tax laws would have spared them.

Congress’s reliance on omnibus bills, which are written in secret, has had a variety of pernicious effects. The procedure violates every rule of good legislative process, denying transparency and accountability. It allows Capitol Hill to curry favor with all sorts of special interests but no public reckoning. It forces — or allows — members to vote for provisions that would have had little chance of surviving on their own. And it puts enormous power in the hands of the leadership of both parties — not least because lobbyists have come to understand that they need to have a representative in the room where the omnibus is crafted, and therefore they focus money and attention on leaders.

The last Congress maintained one other lamentable trend: it took “oversight” to mean injecting its investigations with excessive partisanship — Benghazi, the IRS’s examination of conservative groups, the VA’s mishandling of health care for veterans — while forgetting the crucial, ongoing oversight of government. It allowed itself to be co-opted by the intelligence community, which persuaded Congress to neglect a public debate on massive surveillance, hacked the Senate’s computers, misled Congress about the nature and extent of torture, and leaked classified details to the media.

The congressional leadership is now under pressure to show Americans that they can be successful. Let’s hope they consider “success” to include avoiding the bad habits of the past — by paying more attention to their constituents than to special interests; enforcing their own ethics rules more vigorously; and most of all, following the “regular order” based on 200 years of legislative experience, which would allow the full debate and votes Congress needs to serve as a true coequal branch of government.

Lee Hamilton is Director of the Center on Congress at Indiana University. He was a member of the U.S. House of Representatives for 34 years.