By Theogene Rudasingwa

Photos: YouTube Screenshots\Wikimedia Commons

In 1962, a relatively obscure physics professor at UC Berkeley, Thomas S. Kuhn, published The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. This book would fundamentally alter our understanding of science and knowledge itself. Kuhn challenged the comfortable, long-held belief that science progressed as a smooth, linear accumulation of facts. Instead, he proposed that scientific history is a cycle of stability and radical upheaval.

Kuhn argued that scientists typically work within a shared “paradigm”—a dominant framework of theories, methods, and assumptions that defines legitimate research (what he called “normal science” or “puzzle-solving”). This phase is productive but rigid. Inevitably, anomalies emerge—results that contradict the reigning paradigm. Initially dismissed, these anomalies eventually accumulate to a point of crisis, shattering confidence in the established order. The ensuing scientific revolution, or “paradigm shift,” replaces the old framework with a new, fundamentally incompatible one. This change isn’t purely rational; it’s a messy, generational struggle akin to a political revolution.

Kuhn’s insights provide a powerful lens through which to view the tumultuous state of contemporary world affairs. The current global order is experiencing its own profound “Kuhnian crisis,” with the established paradigm of the last few decades collapsing under the weight of persistent anomalies it can no longer explain or manage.

The prevailing “paradigm” governing international relations since the end of the Cold War has been the American-led liberal international order. Its core tenets—multilateral institutions (the UN, WTO, World Bank, IMF), the promotion of free trade, global supply chains, and the spread of liberal democratic norms—created a period of relative stability and interconnectedness. For a time, this framework enabled remarkable global economic growth and cooperation.

Yet, as with anomalies in a scientific experiment, this paradigm produced systemic failures that it could not adequately address.

The first significant anomaly has been the uneven distribution of globalization’s benefits. While many nations prospered, others faced deindustrialization, increased domestic inequality, and the hollowing out of their middle class. This fueled a widespread loss of faith in the “puzzle-solvers”—the political elites and economists who managed the system.

The second anomaly is the erosion of the system’s foundational institutions. The World Trade Organization (WTO) is functionally paralyzed due to the refusal to appoint new appellate judges, thereby preventing it from effectively enforcing global trade rules. The UN Security Council is a theater of inaction, stymied by great power vetoes on critical issues like the wars in Ukraine and Gaza. These institutions, once seen as the bedrock of a “rules-based order,” are increasingly perceived as irrelevant or biased, no longer fit for purpose.

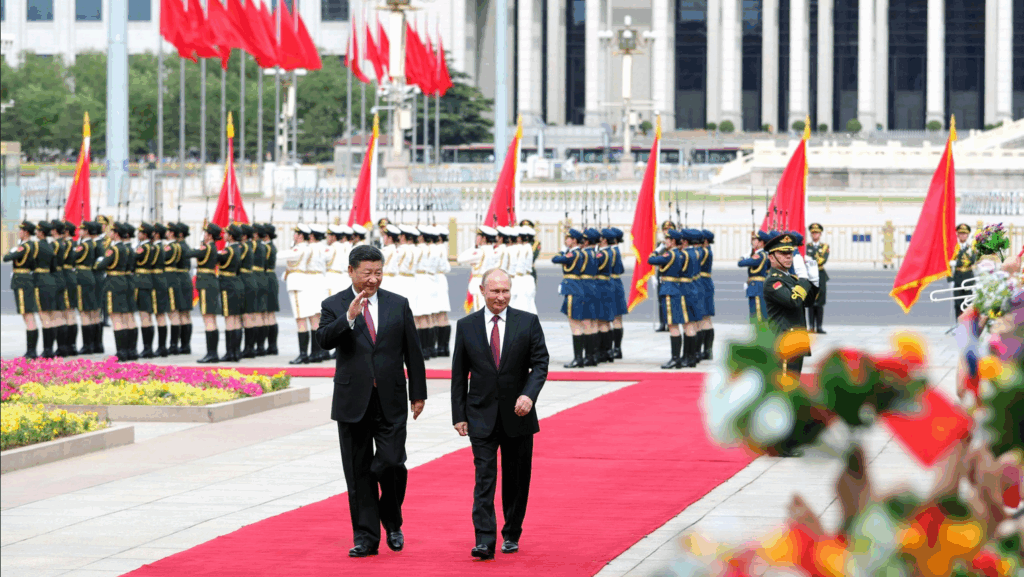

The most potent anomaly, however, is the rise of powerful, illiberal challengers—namely China and Russia—who actively reject the core tenets of the liberal paradigm. They offer alternative models of governance and global influence (like China’s Belt and Road Initiative), creating a geopolitical contest that the existing framework was never designed to handle.

These anomalies have accumulated, pushing the global system into a full-blown “crisis” phase. The characteristic features are evident everywhere: heightened disorder, conflict, and a fundamental questioning of the legitimacy of the old order. We are in a transitional, chaotic period in which the old guard is struggling to maintain control, while challengers are gaining traction.

The “incommensurability” Kuhn described in science is mirrored in the chasm between the world’s major powers today. When U.S. and Chinese diplomats discuss “human rights,” “sovereignty,” or a “rules-based order,” they often use the exact words but operate within entirely different conceptual frameworks. There is no shared foundation of assumptions to bridge the gap, making dialogue difficult and agreement almost impossible. Like scientists from competing paradigms, they talk past one another because they operate with different definitions of “normal” international affairs.

We are, therefore, in the midst of a “geopolitical revolution.” The liberal international order is in terminal decline, but no single replacement paradigm has yet emerged as dominant. The future is uncertain.

Will we witness a new multipolar world characterized by spheres of influence and intense great power competition? Will a non-Western power, such as China, establish a new, alternative system? Or might the world fracture into regional blocs with minimal cooperation?

Kuhn’s work doesn’t predict the outcome, but it warns us that the transition won’t be smooth. It will be characterized by struggle, persuasion, and a mix of evidence and social factors, not just rational decision-making. The current moment is not a temporary deviation from an otherwise stable world; it is the death knell of one era and the painful, messy birth of the next. Understanding this as a Kuhnian paradigm shift helps us recognize that a “return to normalcy” might be impossible, and we must instead prepare for a fundamentally new global order.–